Postpartum Thyroiditis – The Roller Coaster Ride for New Mothers. Having a baby can be one of the most rewarding experiences in a woman’s life. It can also be one of the most exhausting. Up and down all night, unpredictable schedules, added demands and responsibilities – all of these can cause a new mother to feel tired and stressed.

While many women start feeling better anywhere from six weeks to three months after delivery, some will continue to have or develop symptoms, such as fatigue, anxiety, feeling “blue,” poor memory, and lack of concentration.

Developing Postpartum Thyroiditis – The Thyroid Gland

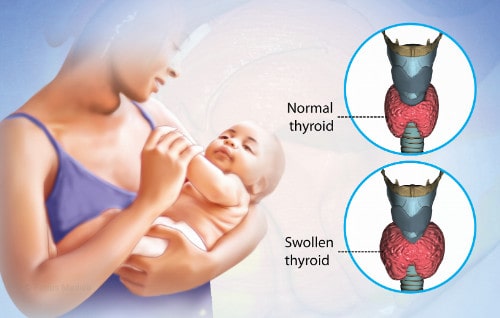

Postpartum thyroiditis is a temporary, painless inflammation of the thyroid gland that occurs within a year after 5% to 10% of all pregnancies. Until the last two decades, there has been little information available about postpartum thyroid dysfunction. However, recent research has demonstrated the need to recognize and, if necessary to treat women suffering from this disorder.

The Course and Risk for Postpartum Thyroiditis

Postpartum thyroid disease occurs within the first year after delivery, usually from eight weeks to four months postpartum. The signs and symptoms of this thyroid dysfunction vary from woman to woman. Typically, the symptoms are mild. In fact, they can be so mild, that many women are unaware that they exist or dismiss them as a normal part of having a baby.

There are three courses that postpartum thyroiditis can follow:

- a hyperthyroid phase followed by a return to normal thyroid function

- a hypothyroid phase alone

- a hyperthyroid phase followed by a hypothyroid phase

HIGH RISK FACTORS FOR POSTPARTUM THYROIDITIS

- presence of a goiter

- high levels of antithyroid antibodies during the first trimester

- history of postpartum thyroiditis after previous pregnancies

- strong family history of autoimmune thyroid disease

- Type I diabetes

Signs and Symptoms of Postpartum Thyroiditis (Hypothyroid) Phase

During the hyperthyroid phase, the thyroid gland cannot control the release of thyroid hormones it normally stores. Therefore, too many thyroid hormones are released into the bloodstream. Although some women do not experience any symptoms of hyperthyroidism, others can have one or more of the following signs and symptoms:

- goiter (an enlarged thyroid gland)

- fatigue

- nervousness

- irritability

- feeling hot

- rapid heartbeat

- inability to concentrate

- trembling hands

- muscle weakness

- weight loss (metabolic disorders)

The hyperthyroid phase lasts approximately eight weeks or until the thyroid hormones supply decreases. In some cases, the gland recovers and returns to normal function.

The Lack of Thyroid Hormones can lead to Hypothyroidism

If there is sufficient damage to the thyroid gland following the hyperthyroid phase, it may be temporarily unable to produce enough thyroid hormones, resulting in hypothyroidism or underactive thyroid. Other women with postpartum thyroiditis do not go through a hyperthyroid phase; they only develop hypothyroidism.

During the hypothyroid phase, a woman could have one or more of the following signs and symptoms of postpartum thyroiditis:

-

- goiter (an enlarged thyroid gland)

- fatigue

- depression

- poor memory (impaired concentration)

- feeling cold

- constipation

- muscle cramps

- difficulty losing weight (weight gain)

- dry skin

The hypothyroid phase can begin between the third and eighth month after delivery and is usually temporary, lasting up to six to eight months. However, approximately 25% to 30% of the women who have postpartum thyroiditis symptoms will eventually develop permanent hypothyroidism.

Thyroid Dysfunction Causes

Researchers do not know precisely what causes the thyroid gland to become inflamed after a woman delivers a baby. However, they do know that certain antithyroid antibodies (TPOab) are often present in the bloodstream of women who develop postpartum thyroiditis.

This finding indicates the possibility that postpartum thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease. When someone has an autoimmune disease, his or her body’s immune system incorrectly identifies the cells of normal body tissue as “invaders” and then produces antibodies to attack these cells.

During pregnancy, the immune system becomes somewhat suppressed, possibly to prevent the formation of antibodies that could harm the fetus. After delivery, the immune system reactivates. It is during this time that the immune system can produce antibodies that attack the thyroid gland.

As many as 30% to 50% of the women who have TPOab in their blood during the first trimester of pregnancy will develop postpartum thyroiditis. Dr. J.H. Lazarus and his colleagues did a yearlong postpartum symptoms study of 152 women with TPOab and 239 women who did not have TPOab.

None of the 239 women who had negative TPOab measurements developed postpartum thyroid dysfunction. Among the women positive for TPOab, 48% developed postpartum thyroiditis. Of this group, 19% developed hyperthyroidism followed by recovery, 49% had hypothyroidism not preceded by hyperthyroidism, and 31% experienced a hyperthyroid phase followed by a hypothyroid phase.

Postpartum Depression

Interestingly, the researchers confirmed previous studies indicating an increased incidence of postpartum depression symptoms among women positive for TPOab.

TPOab are present in women with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, and Type 1 diabetes. Therefore, it is not surprising that these women develop postpartum thyroiditis. Studies have shown that women with Type 1 diabetes are particularly at risk for developing postpartum thyroiditis. In addition to indicating the likelihood of postpartum thyroiditis, the presence of TPOab also indicates an increased risk of miscarriage.

Even though not demonstrated in the Lazarus study, postpartum thyroiditis can occur in women who do not have anti-thyroid antibodies. Therefore, researchers suspect that there are further causes as yet undiscovered. More research to determine the reason women develop this disorder.

How is Postpartum Thyroiditis Diagnosed?

The hyperthyroid phase can be diagnosed by measuring thyroid hormone levels in the blood. A low TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) and a high T4 level indicate hyperthyroidism.

To distinguish between postpartum thyroiditis and Graves’ disease, the leading cause of hyperthyroidism in North America, a physician can order a radioactive iodine uptake test. Since Graves’ disease causes an overactive thyroid gland , the results of the uptake will be high. However, postpartum thyroiditis damages the thyroid gland, and the uptake will be low.

Radioactive iodine can get into breast milk. Therefore, a woman who is nursing will need to discontinue breast feeding for three to five days, or she and her physician may elect to delay the procedure.

Hypothyroidism is also diagnosed by measuring high thyroid hormone levels. A high TSH measurement and a low T4 level will confirm the diagnosis of an overactive thyroid.

How is postpartum thyroiditis treated?

Sometimes the most important treatment for postpartum thyroiditis is recognizing that it exists. Most women are relieved to know the reason for their discomfort and that it is temporary.

Women who have hyperthyroidism during postpartum thyroiditis do not require the same treatments usually offered to women who have permanent forms of hyperthyroidism. If they are suffering from tremors and a rapid heart rate, beta-blockers may help.

Women who have hyperthyroidism during postpartum thyroiditis do not require the same treatments usually offered to women who have permanent forms of hyperthyroidism. If they are suffering from tremors and a rapid heart rate, beta-blockers may help.

Beta-blockers do not affect thyroid function, but they do provide significant symptoms relief during the short duration of these phases.

Treatment during the hypothyroid phase depends upon the severity of the significant underactive thyroid symptoms and how abnormal the low thyroid hormone levels are.

Levothyroxine

Many endocrinologists prescribe levothyroxine, a synthetic thyroid hormone, to help restore normal thyroid hormone levels (see Volume III, Number 2, Summer 1997 of The Thyroid Connection).

Women take a small pill of levothyroxine once a day for approximately six months. If a woman is nursing she can safely take levothyroxine because only minimal amounts get into breast milk. To determine if hypothyroidism is temporary or permanent, a woman must discontinue her levothyroxine for approximately four to six weeks in order to retest TSH and T4 levels. If she is one of the 25% to 30% of women who develop permanent hypothyroidism after postpartum thyroiditis, she will take levothyroxine once a day for a lifetime.

Several studies by the American Thyroid Association have indicated that there are some factors that can predict whether hypothyroidism will be permanent. They include the following:

- a hypothyroid phase that is not preceded by a hyperthyroid phase

- high TPOab levels

- TSH levels over 20

Some physicians prescribe levothyroxine indefinitely for women even though test results indicate normal thyroid function has returned. They hope that indefinite treatment with levothyroxine will minimize recurrent postpartum thyroidism during subsequent pregnancies.

However, this is not supported by research data, and Dr. Susan Mandel of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania does not advocate this approach. “Women who take levothyroxine indefinitely and develop a second episode of postpartum thyroiditis after a subsequent pregnancy are more likely to experience hyperthyroid symptoms.” The American Thyroid Association recommends long-term follow-up of postpartum thyroiditis patients with annual or bi-annual rechecks via a thyroid blood test.

THYROID FACTOIDS

- Postpartum thyroiditis occurs in 5% to 10% of women after they give birth.

- The presence of antithyroid antibodies (TPOab) in a woman’s bloodstream significantly increase her risk for miscarriage and postpartum thyroiditis.

- As many as 30% to 50% of the women who have TPOab in their blood during the first trimester of pregnancy will develop postpartum thyroiditis.

- TPOab are usually present in women with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, and Type 1 diabetes, increasing their likelihood of developing postpartum thyroiditis.

- Postpartum thyroiditis can also occur in women who do not have TPOab, but it is less common.

- 25% to 30% of women who have had postpartum thyroiditis will develop permanent hypothyroidism within five years after they deliver.

- If a woman experiences postpartum thyroiditis in one pregnancy, she is likely to develop it in subsequent pregnancies.

Screening

“The value of screening for postpartum thyroiditis and the best test to use for prenatal screening are unclear,” according to Dr. Mandel. There is no consensus among physicians about whom to screen and when to screen for it.

Some physicians recommend screening for all pregnant women for postpartum thyroiditis by periodically measuring TPOab and/or TSH. Others prefer screening women at high risk for postpartum thyroiditis. Dr. Mandel conducts thyroid function tests among the following patients:

- women with autoimmune disorders, such as Type 1 diabetes, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis

- women with a strong family history of thyroid disease

- women with goiters

- women with a previous history of thyroid problems

For these patients, she recommends checking for thyroid antibodies and measuring underactive thyroid hormone levels in the first trimester with a recheck of thyroid hormone levels three months after delivery.

Conclusion

Postpartum thyroiditis is a relatively common disorder that has previously been unrecognized and untreated. Although symptoms are temporary and usually mild, most women are relieved to learn that their symptoms are not all in their heads, that they are not “losing their minds,” that they don’t have a life-threatening disease, and that there are inexpensive, effective treatments to relieve their discomfort.

A healthy, well functioning thyroid gland is important to everyone, but it is especially important to women in their childbearing years. A woman’s thyroid status not only affects her health status but can have a significant impact on the health and the well-being of the children she bears.

A recent study suggested that inadequate underactive thyroid hormone during early pregnancy could adversely affect their child’s intelligence (see Volume IV, Number 3, Autumn 1999 of The Thyroid Connection).

The presence of thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies can further complicate a woman’s health. In addition to increasing the risk of developing postpartum thyroiditis, the presence of antithyroid antibodies has been linked to an increased incidence of infertility, miscarriage, and postpartum depression.

Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

Since approximately 90% of the women who develop postpartum thyroiditis eventually develop Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, confirming the presence of antithyroid peroxidase antibody (aka Etiology Postpartum thyroiditis) could help determine which women are at risk for developing both disorders. Early detection of either disease shortens the duration and extent of suffering a woman would otherwise endure.

There are unanswered questions about the cost effectiveness of screening women for postpartum thyroiditis as well as who to screen, when to screen, and how to screen for this disorder. It is time to answer these questions, to unravel the mysteries of postpartum thyroiditis, and to determine an effective, inexpensive way to identify pregnant women who are at risk for thyroid diseases.

Accomplishing these goals will require the cooperative efforts of the general public, government agencies, the medical industry, and medical professionals to participate in and support funding for thyroid research.

As a result, ways will be found to diagnose and treat thyroid diseases that could adversely affect women’s ability to have children at a childbearing age, put them at risk for needless suffering, or damage their unborn children’s potential.